Planning and designing long term care and health care facilities: a person centered approach

When designing a care environment, people – in this case residents in long-term care settings and patients in acute care settings, as well as the caregivers – should be at the centre of the entire process. This focus is essential to achieve an attractive and efficient environment that stands the test of time.

There are 7 factors to consider when designing healthcare facilities:

- Planning healthcare facilities for mobility and flexibility

- Planning healthcare facilities for the resident

- Planning healthcare facilities for the caregiver

- Planning healthcare facilities for physical overload: minimising the load

- Planning healthcare facilities for efficient care

- Designing healthcare facilities based on number of caregivers

- How to approach designing long term care and healthcare facilities

Planning healthcare facilities for mobility and flexibility

An effective and efficient care environment needs to facilitate patient and resident mobility. This means that the space and layout should allow for the ergonomic use of mobility aids and equipment that enable patients and residents to participate in daily activities and personal care routines.

As a natural part of the aging process, over time elderly residents may become increasingly dependent on caregivers to perform their daily activities. As such, their care environment needs to be adaptable for different residents with different levels of mobility, as well as different levels of cognition.

Planning healthcare facilities for the resident

Getting residents out of bed regularly and helping them to sit, stand, or walk around, has proven to have significant physical and psychological benefits1. Getting out of bed stimulates a resident's cognitive function as well as vital bodily functions such as the heart, lungs, bladder, bowel, bone and muscular structure, and blood circulation. Mobility has been shown to reduce the risk of a number of medical complications, such as pressure injuries, depression, infection, eating problems, and a rapid decline in muscle strength and skeletal structure2.

Daily hygiene routines provide a very important opportunity to mobilise the resident. Residents usually prefer to go to the toilet to empty bladder and bowel, even if they are incontinent, as well as being able to experience a proper shower or bath. By using all possible opportunities to provide stimulation and activity, we can help residents be more active and alert, and help to facilitate the many positive effects of maintaining mobility.

Planning healthcare facilities for caregivers

For caregivers, having sufficient space and the right equipment to support resident mobility can yield more active and alert residents. A more active resident requires less assistance, which can lead to reduced risk of strain and related injuries. This improves the caregiver’s well-being, allowing them to provide better quality care. Another implication is the improvement of staff retention, fewer sick days, and higher overall job satisfaction, which in turn leads to a reduction in costs for the care facility.

As demand for quality healthcare continues to grow, so will the demands placed upon caregivers. Attracting and motivating caregivers should be a priority, and a well-designed work environment can be a significant factor.

For the caregiver, it is important to be able to perform tasks as efficiently as possible while minimising the risk of injury. While the care situation may vary, each lift, transfer and forward bending activity poses some risk of physical overload, and a badly planned work environment only compounds this problem.

Caregiver is a blanket term for all the people who support the resident in the care facility. A common factor for all caregivers is that they work in an environment which is another person’s home – often the last home in that person’s life.

Design planning for healthcare facilities for physical overload and minimising the load

The risk of injury increases when there is insufficient space to allow the use of proper equipment and techniques. Two primary hazards have been identified in ergonomic studies: dynamic overload and static overload.

Minimising dynamic and static overload is key to reducing physical strain and the risk of injury for caregivers.

Dynamic load is the load placed on the caregiver's body related to movements such as pushing, pulling, lifting etc. Static loads are those experienced by the caregivers due to postural strain, in other words, when they are not working in an ergonomic posture, for example by having to bend over a patient to assist with feeding, or to wash them in bed.

Minimising static overload is achieved by ensuring the caregiver is able to work in an optimal working posture, and spends as little time as possible in a forward bending position. This is done by providing height adjustable equipment, for example, beds, bath tubs and shower chairs3 4.

Dynamic overload is minimised by lifting and transferring patients with the help of the right equipment, such as patient lifters, instead of performing these tasks manually5 6 7.

Planning healthcare facilities for efficient care

One way to compensate for at least some of the growing need for more caregivers, without compromising on care quality, is to improve caregiver efficiency. The right equipment, ergonomic working techniques and a well-planned care environment all help to facilitate efficiency.

It may also be important to introduce care procedures that require only one caregiver, instead of two or more. Helping the resident maintain or improve their independence will also contribute to this efficiency process by reducing their dependence on caregiver assistance.

Planning healthcare facilities for number of caregivers

Modern resident handling and hygiene equipment is often designed for use by a single caregiver. The single caregiver approach may also enable the resident to receive more personal attention, and facilitate a calmer care situation. Single handed care may also be efficient, as the caregiver does not have to wait for a colleague to assist. Some policies dictate that two caregivers are needed to transfer a resident with a patient lift, however, typically in these situations the second caregiver may take a passive role in supervising the resident. The space requirements recommended in our architectural guidelines have not considered a second caregiver. Exceptions may include additional support for plus size residents or patients with cognitive or behavioral limitations.

How to approach planning and designing healthcare facilities

Arjo has worked closely with care facilities to gain valuable insight into their care routines and challenges, as well as the factors that need to be considered in the first stages of planning and designing a care environment. By considering the needs of the resident, the caregiver, and the operational requirements of their equipment, we have developed a number of visual tools and examples to help make the most of every square metre.

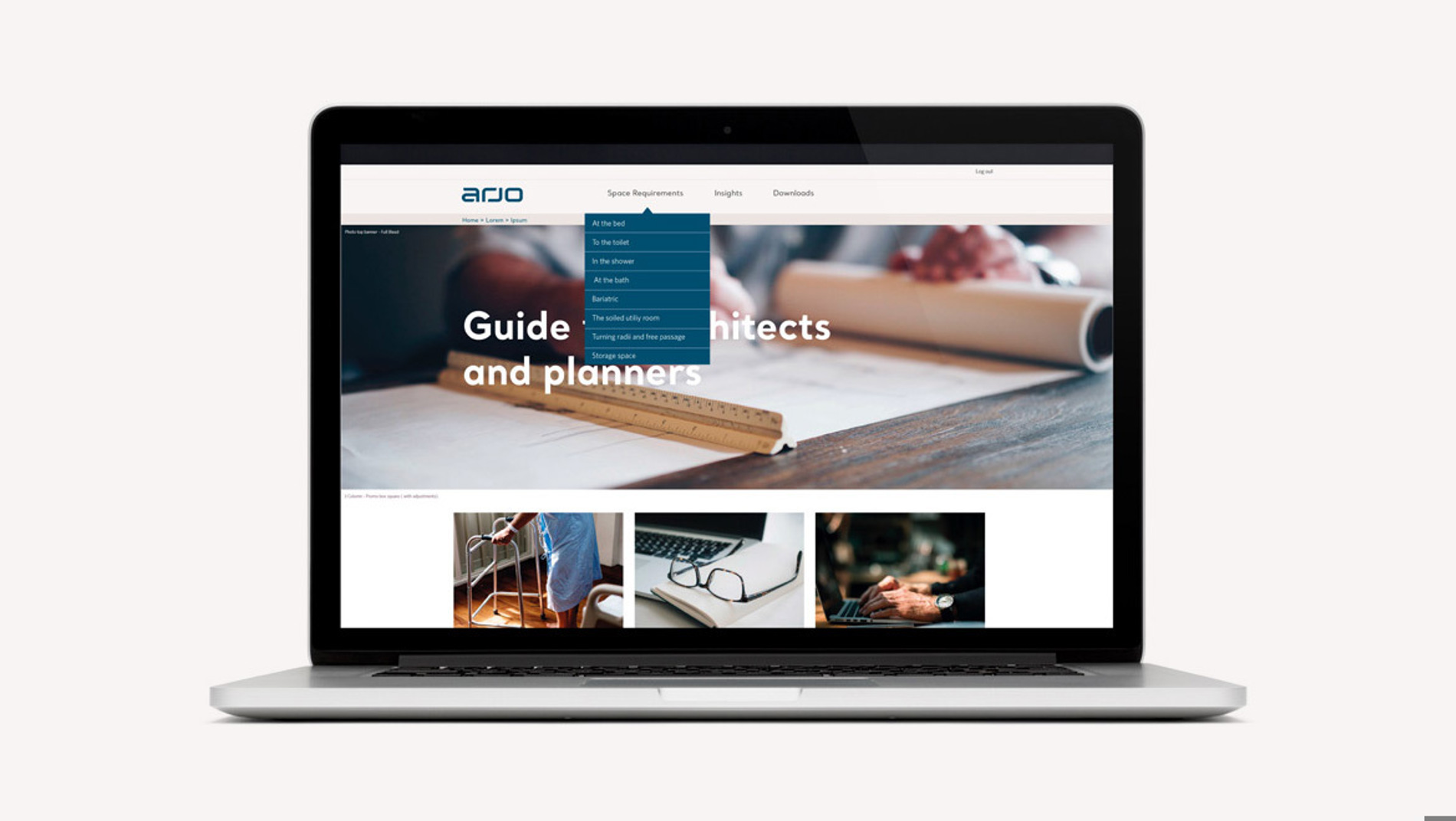

Architect Portal

We have developed a comprehensive selection of plan drawings detailing the minimum required working space needed for caregivers to be able to use the necessary mechanical aids as intended. These drawings depict individual care situations rather than full rooms, so that they can be selected and combined to suit any facility floor plan. However, complete drawings are also available for ideal room types, such as resident rooms, bathrooms and soiled utility rooms, to provide a planning guideline.

References:

1. Gucer et al 2013

2. Stuempfle and Dury, 2007

3. ISO Standard 11226, 2000

4. Freitag, 2007

5. CEN/ISO TR 12296

6. Nelson et al, 2009

7. Waters, 2007